Vernita “Nita” Watts

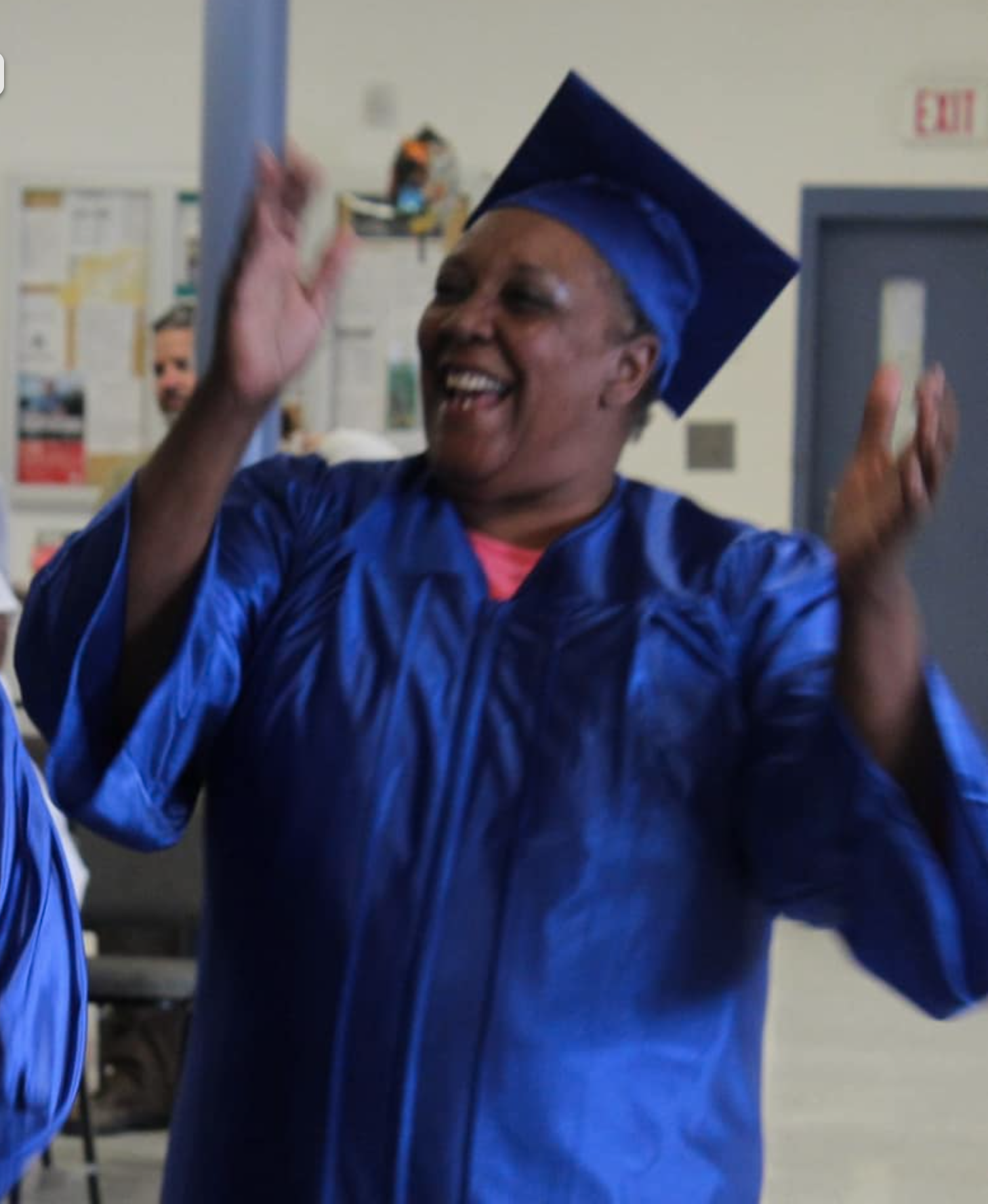

Photograph of Vernita Watts (center), obtained from the RISE program.

On September 16th, 2020, Vernita Watts passed away after a monthslong battle with COVID-19. Known as a choir instructor, prayer warrior, and master braider, Vernita was a beloved presence in the community with a knack for bringing people together. She was seventy years old when she died.

Vernita discovered her love of braiding in California in the 1970’s, where she met a close-knit group of women who opened a hair salon known as The Braidery. She learned to braid hair from the salon’s founder, Linda Hoffman, and within a few years, she had become one of the most popular stylists at The Braidery. “We were pioneers of the braid industry who changed the way people view the art of braiding,” Linda recalled on Vernita’s GoFundMe page created by her son Don Emerson Jr.. “She mastered the techniques and became one of the best respected braid artists on the West Coast.”

Even as Vernita spent the last years of her life behind bars, she kept her love of braiding alive. In the summer of 2017, Vernita graduated from the RISE cosmetology program at the Mabel Bassett Correctional Center in McLoud, Oklahoma, with a specialization in cutting hair. Later that year, she passed the exam to become a Master Instructor. “It's like I'm not in prison for the hours that I'm in the classroom,” Vernita said of the program before she passed away. “I get to help the girls who've never done this before."

Beyond braiding hair, Vernita was a mentor and dear friend to many women at Mabel Bassett. In the comments of a Facebook post from the RISE program, Vernita’s friends and acquaintances remember her as a wonderful woman who cared deeply for those around her. Kirsten Smith, who sang in the church choir that Vernita led, wrote that Vernita “knew how to make me smile every time I was nervous on stage.” Jacque Harjo-Putman recalled that “[Vernita was] the very first person I met in prison. When my father died, it was Nita Rita who held me while I cried.”

Now, Jacque is among the loved ones mourning Vernita’s death. The news of her passing brought forth an outpouring of emotion from women who knew her at Mabel Bassett and at Eddie Warrior Correctional Center, where she was transferred shortly after graduating from RISE. “My heart is broken,” Liza Sanchez wrote on the RISE Facebook page, who was Vernita’s bunkie at Mabel Bassett. “I’m going to miss her so much.”

Photograph of community members holding up messages of support outside Eddie Warrior Correctional Center, courtesy of Chris Polansky, by way of Public Radio Tulsa.

In contrast to the condolences that Vernita has received from friends and family, the Oklahoma Department of Corrections (DOC) has remained silent on her death. Although the agency acknowledged that an individual at Eddie Warrior had passed away in September, it refused to disclose their identity or attribute their death to COVID-19, citing the need to wait for medical confirmation. But one day after the DOC’s announcement, Vernita’s status on the state prison database changed from “active” to “inactive,” suggesting that Vernita was indeed the individual mentioned in the report. And her son confirms on her GoFundMe page that Vernita passed away from the coronavirus, fighting the disease with “every ounce of her body” for over a month in the ICU.

The DOC’s silence on Vernita’s death is consistent with its lack of transparency on other coronavirus-related matters, which advocates say is directly responsible for the spread of the disease. Despite 1,639 incarcerated individuals having tested positive for COVID-19—780 of them at Eddie Warrior, which has a maximum capacity of 1,000—the state has yet to hold a press conference on the spread of the virus in correctional facilities. On the Friday before Vernita’s death, seventy-five community members rallied outside the chain-linked fence enclosing Eddie Warrior, calling for Governor Kevin Stitt to require staff testing and allow early release for vulnerable individuals. “I can’t sleep,” said Tiffany Walton, a lead organizer for the protest who felt called to action after seeing her patients die of COVID while working as a nurse. “They didn’t get a sentence to die. They don’t deserve to die.”

On the RISE Facebook page is a photo album commemorating one of Vernita’s proudest moments—her graduation from the RISE program. In one of the photographs, she is shown smiling and clapping in a royal blue cap and gown, putting her signature full-bellied laugh on display. Beneath the image, AJ Watkins, one of Vernita’s classmates at RISE, wrote, “What an awesome pic[ture]... that’s how I imagine her arriving at our Father’s house.” We join AJ, Liza, and others in honoring Vernita’s memory—and in celebrating her triumphant return to her Father’s arms.

Photograph of Vernita Watts, obtained from the RISE program.

This memorial was written by MOL team member Mirilla Zhu with information from the RISE program on Facebook, Chris Polansky of Public Radio Tulsa, and a GoFundMe organized by Don Emerson Jr.