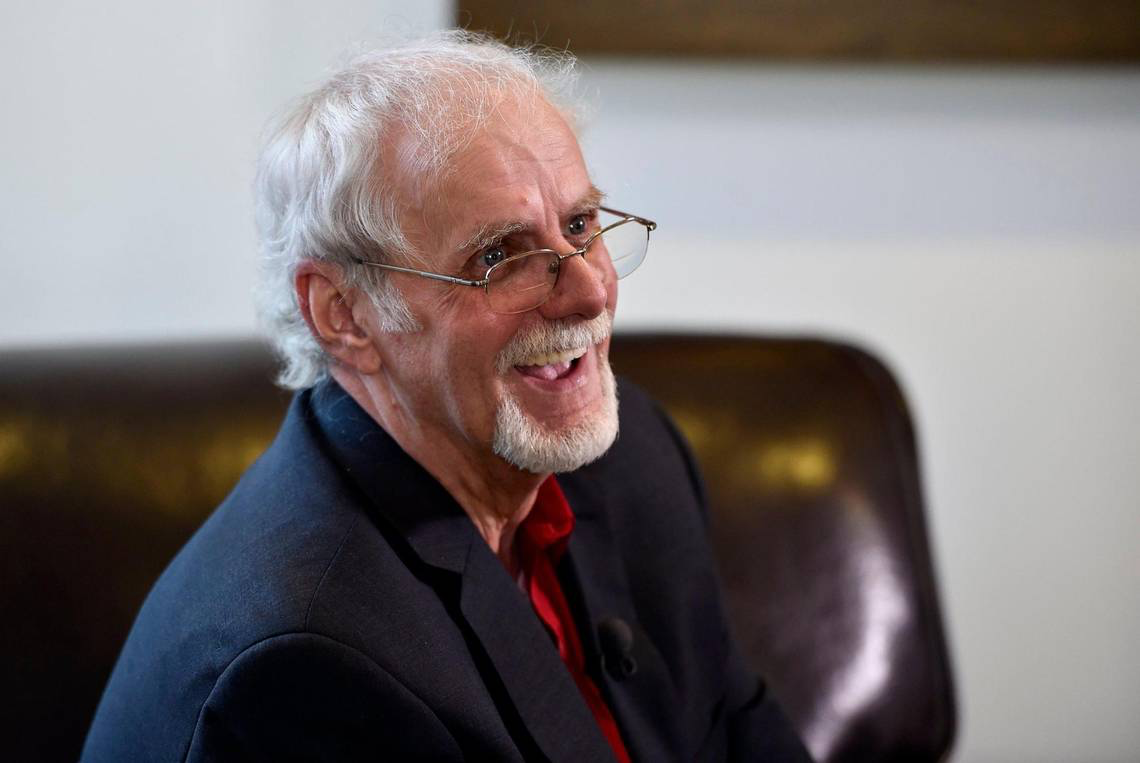

Olin “Pete” Coones Jr.

Photograph of Olin “Pete” Coones, courtesy of The Kansas City Star.

Nothing captures Olin “Pete” Coones Jr. better than the words “family man.” Commitment to family shaped and sustained Pete, who chose to live lovingly and strove to set a good example for his children and grandchildren. He did so in spite of what the Midwest Innocence Project describes as “the decade he should have had to spend with his family and loved ones [...] the upcoming birthdays, anniversaries, and holidays they should have shared with him.” Hailing from Piper, Kansas, he built his family in Kansas City, Kansas, with his wife, Dee, who he lauded as “something special” and credited with keeping him going even without realising it. Together they raised five children - Jeremiah, Ben, Quinn, Mariah and Melody - and warmly welcomed grandchildren. Pete had worked as a mail carrier and, upon retirement, utilised his increased free time to enjoy his family’s company, play music and go fishing.

Pete lost twelve years of his life when he was wrongfully convicted. No physical evidence tied him to the crime and he’d had an alibi, but in the face of prosecutorial malpractice, manufactured and hidden evidence, and the use of a jailhouse informant’s testimony, the truth was not enough. Pete was left shackled to an unjust sentence of life imprisonment. Every prayer of Pete’s was devoted to the hope of returning home to his family. His small source of solace was that, in his words, “I didn’t need a miracle, I just needed the truth.”

Twelve years too late, discoveries made by Pete’s attorneys - largely of evidence that had been available at the time of prosecution - proved enough to arrange an innocence hearing. His was the inaugural innocence claim to go to court under District Attorney Mark Dupree’s conviction integrity unit, the first of its kind created in Kansas. Even the judge cried as Pete’s free place in society was restored at long last on November 5, 2020. Pete spoke of his release with the utmost gratitude, noting that he “got a miracle of truth, and so, that’s a double blessing.” His Facebook profile gleefully reads: “Happy and thankful to be free!” It seems Pete was even surprised by the depth of his own generosity and love, remarking that “I don’t hate anybody. I’m not mad at anybody. I was sure I would be.”

Though saddled with extreme hardship, to Pete the people hardest hit by his conviction, and the true victims of his incarceration, were his family. He eagerly anticipated taking things slowly, spending as much of his time with his family as possible and reacquainting himself with his hobbies such as fishing and playing the drums. Brimming with love and joy, Pete, finally armed with some control over his present, looked unwaveringly towards the future. With his loved ones to restore him, Pete visualised his life and reconciled the years he lost: “A few years down the road, it’s just a speed bump in the rear view mirror.”

Photograph of Pete with his wife Dee and children, courtesy of KCTV, Kansas City. by way of MSN.

Tragically, only 108 days into his long-awaited freedom, Pete died from cancer on February 21st, 2021 aged just 64 years old. Though his spirit proved enduring, Pete left prison “in a body that was broken,” in the words of his attorneys. Evidence suggests that he ultimately succumbed to health conditions that went undiagnosed and untreated during his time in prison. Pete had so much life left to live; his world was still unfolding. He met his grandchildren for the first time and was smitten with them. This bittersweet, ephemeral stint of freedom provides little consolation to his grief-stricken family, who take only a small measure of comfort that Pete died a rightfully free man.

Pete was deeply concerned with the example he set for others. Speaking just days after his release, he affirmed that,“[I am] so perfectly content with my decisions that I can sit here in this chair and tell you that I was offered a five-year plea deal, and I didn’t take it.” He wasn’t even aware of what he would have had to plead guilty to; for him, it was out of the question to prioritise his potential personal gain over the truth. He turned down the deal because he personally felt unable to tell his children that “it’s okay to raise your hand and say you did something, swear an oath and know that you’re telling a lie because the world should never run on lies, the world has to run on the truth.” Though he would’ve loved nothing more than to come home, he refused to consider a plea because it would have forced him to say he did something he didn’t do. Being known only through conviction, particularly in Pete’s case where it was a wrongful one, greatly bothered him.

He recounted a visit from a grandson with a dog who lived in a cage, who asked “Grandpa, why do they keep you in a fence?” This proved too much for Pete to bear, who told his family, “Nope, that’s it. Don’t ever mention me again. Don’t bring them back.” Once free, Pete could finally be the version of himself that he was most proud of. But sadly, Pete’s diminished physical state, a legacy of his maltreatment, was enduring and irrevocably curtailed his long awaited opportunity to set an integrous example for his family.

Photograph of Pete following his exoneration, courtesy of The Innocence Project.

Pete’s family and attorneys say that they will “keep demanding justice in his memory.” Pete never stopped thinking about those left behind. It spurred him on to work and do interviews to talk about the injustice that marred his life, resolving that “Somebody has to say enough. And pay the price it takes to get people to listen.” This was not an easy thing to subject himself to, but through it all Pete “just wish[ed] Dee and the kids could be immune.”

Pete and his family will never get back the years that were taken from them. But Kansas can learn from his case and protect other Kansans going forward. The family hopes to bring about a law in his name to regulate the use of jailhouse informants, measures they believe would’ve kept Pete out of prison in the first place. One of Pete’s attorneys, Lindsay Runnels, described Pete as thoughtful and generous, saying he was excited to become a part of the innocence movement and to play a role in helping change legislation about the use of incentivized informants. Pete believed that Kansas desperately needed to create a system to track its use of jailhouse informants, a growing and pertinent issue: since 1966, more than 140 people in the United States have been exonerated in murder cases that involved jailhouse informants. To Pete, it was simple: “What happened to me is wrong. It shouldn’t happen to anybody.”

For so long, Pete tried to get his family to disentangle themselves from the pain that his wrongful incarceration caused them all. Speaking in an interview with The Kansas City Star, he remembers these habitual conversations with his wife Dee, saying, “I spent 12-and-a-half years trying to talk her into divorcing me, so she could move on with her life because I loved her so much,” continuing, “I didn’t want her to be sad and lonely. And I finally had to shut up on that because she’d get mad at me every time I’d bring it up.” Devastatingly, after more than a decade of denied union, this pain and loneliness was rendered permanent. Pete deserved a lifetime to love and be in the love of his family. We, along with those most dear to him, deeply mourn his passing. May his example live on to guide us all.

Photograph of Pete, courtesy of The Kansas City Star.

This memorial was written by MOL team member Cecile Ramin with information from Pete’s Facebook profile, reporting by Rachel Olding from The Daily Beast, David Medina of KSHB Kansas City, McKenzoe Nelson of KSHB Kansas City, the Midwest Innocence Project, Luke Nozicka, Jill Toyoshiba and Tammy Ljungblad of The Kansas City Star, Melinda Henneberger of the Kansas City Star, Emily Crane of Daily Mail.com, and an opinion piece by Tricia Rojo Bushnell, the executive director of The Midwest Innocence Project, which represented Pete Coones in his exoneration.

You can support Pete’s family by donating to their GoFundMe here.